ORLANDO, Fla. — While tariffs and inflation grab headlines, Chris Kuehl, chief economist for Armada Corporate Intelligence, says 2025’s real economic story involves a trio of interconnected forces that will directly impact drycleaning operations: wildly divergent consumer behavior, an accelerating labor crisis, and the rise of automation.

His 2025 Clean Show presentation, “Economic Outlook: What to Expect in 2025 and Beyond,” paints a picture of an economy splitting into distinct tiers — and the need for dry cleaners to understand which customers they’re serving.

The Three Tiers of Society

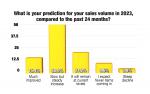

The American consumer market has fractured into three distinct groups, Kuehl says, and they’re driving very different economic outcomes. For dry cleaners, understanding which tier makes up their customer base could determine their pricing strategy and service offerings.

The upper third — households making over $100,000 a year — has barely reacted to inflation. “They see it, and they complain about it,” Kuehl says, “but they’re like, ‘Whatever. I’m not going to change my habits.’”

He shared an anecdote from a car dealer client. A customer came in looking at an $80,000 BMW, disappeared for a few months, then returned. During that time, the same car had jumped to $120,000. When the dealer asked if the buyer still wanted it, the buyer said that he did: “I know it’s $120,000. I can read. I’m rich, I’m not an idiot.”

Kuehl says the buyer then explained his logic: “That car is not transportation. I know I can get a cheaper car. That’s a status symbol. And the fact that it went up in price is a good thing. I have a four-car garage, but that car is never going to be in it. It’s going to be parked in my driveway so my neighbor can look out his window and see it.”

This upper third controls significant spending power. The boomer generation alone controls 60% of U.S. wealth, Kuehl says, and they’re starting to look at the “great wealth transfer” — though the old rules don’t apply anymore.

“When I was a kid, people passed away in their 60s and you were giving your son your house,” Kuehl says. “Now, if you’re a boomer, you might say, ‘Well, son, do you want my house?’ and he’ll say, ‘Dad, I have a house. I’ve had one for a long time.’”

Some boomers are simply spending their wealth rather than passing it on. Kuehl describes a friend who bought his grandson a massive cabin cruiser even though the grandson lives in Scottsbluff, Neb. “The government wants to tax my inheritance,” Kuehl’s friend explained. “I don’t want them to tax my inheritance, so I’m spending the money.”

For dry cleaners serving affluent neighborhoods, this trend suggests continued strong demand for premium services, regardless of price increases. These customers view quality dry cleaning as part of maintaining their lifestyle and status, not as a discretionary expense to cut.

The middle third continues to spend as long as their jobs are secure. “As long as you have a job shortage, which you do in a lot of sectors, that group still spends,” Kuehl says. Even threats of layoffs don’t worry them much when multiple employers are desperate for skilled workers.

This middle tier represents many dry cleaners’ core customer base — professionals who need cleaned business attire and have stable employment. As long as the labor shortage continues, this group should remain reliable customers.

The bottom third — those making $50,000 or less a year — has no money. “They’re living paycheck to paycheck,” Kuehl says. “They can’t buy a car. They know they can’t buy a car. They’re not even looking.”

For dry cleaners in lower-income areas or those offering budget services, this trend suggests increasing pressure as this customer segment has less discretionary income for services like dry cleaning.

The Real Labor Crisis

The workforce shortage that business owners regularly identify as their top concern extends across virtually every sector — including dry cleaning — and it’s getting worse.

Kuehl recounted a client’s experience when interviewing to fill a machinist position that paid over $100,000 with bonuses. Ten years ago, the client said that the job attracted 100 applicants. This time, there were two. “This guy walked into his office and says, ‘This is what you’re going to pay me, this is what my bonus is going to be, and I’m taking a vacation next week,’” Kuehl says.

When the employer expressed shock, the applicant responded: “You’ve got five minutes to make the call, buddy. If you don’t hire me, I’m going to go across the street.”

“And what was the employer’s response?” Kuehl asks. “’I hired both of them. And I paid what they asked, which was a third higher than I planned to. What choice did I have?’”

This scenario might be familiar to drycleaning owners struggling to find counter staff, pressers and route drivers. The labor shortage gives workers much more leverage in wage negotiations, Kuehl says, and competing employers are often willing to pay more.

The long-term outlook gets worse. With every boomer reaching retirement age by 2030 and Gen X leaving early, the resulting demographic collapse will reshape every industry — including dry cleaning, where experienced workers are already hard to replace.

For drycleaning business owners, this means workforce challenges will likely define competitive advantage more than any other factor in the coming years. Cleaners who can’t attract and retain staff may struggle to maintain service levels, while those that solve the labor puzzle through higher wages, better conditions, or automation will gain market share.

Come back Thursday for the conclusion, where Kuehl discusses the automation revolution and what the economic outlook could mean for drycleaning businesses.

Have a question or comment? E-mail our editor Dave Davis at [email protected].