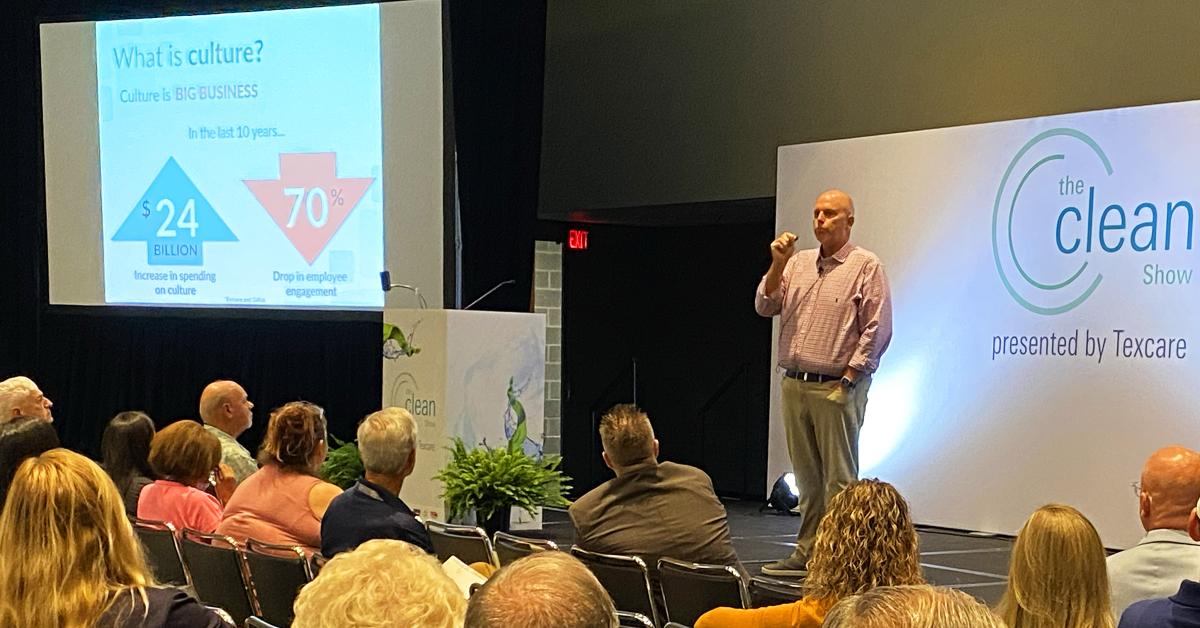

ATLANTA — The term “culture” has come to mean many things to different people, and for business owners, the keys to creating a “winning culture” have become big business to those claiming to know the secrets to quickly building that atmosphere.

During his presentation “Best Culture Wins” at the 2022 Clean Show, Sean Abbas cautioned owners not to fall into this mindset. Abbas, president of Threads, Inc., a software company he co-founded to help organizations review employees on culture, offered his views on this subject, and noted that positive cultures are generated over time and with a great deal of forethought.

In Part 1 of this series, we examined some of the benefits of having a positive culture — and some of the pitfalls that come with “quick-fix” solutions. Today, Abbas details some of his own experiences — and the moment he rethought a major part of leadership.

Real-World Experience

After serving in the U.S. Marine Corps and then graduating from college, Abbas started working at an industrial laser manufacturing company — a startup, where he was the company’s ninth hire. “The pay wasn’t all that great, but what was so cool when I interviewed with the company, all eight people were at the interview and asked me questions.”

When explaining the job to his wife, Abbas told her that, while the pay was low, he sensed something special about the company, and that it would grow quickly: “I told her ‘I just love this place. It just I feel at home there. I’m excited to go there. I want to be a part of this thing.’”

After a few years, the nine-person company grew to be a 90-person company. While that growth was positive, Abbas noted that the feeling of the place started to change.

“What happens, when a business starts small, is that it’s really cohesive,” Abbas says. “As it grows, it starts getting employee handbooks and policies and procedures, and the employees start saying things like, ‘This isn’t a family environment anymore.’”

The company stopped growing at this point, Abbas says, not because of the economic conditions, but because there had started to be a disconnect between leadership and the employees. At this point, Abbas had grown into a sales and marketing position, and the board asked him to be the president of the company.

“They said, ‘We need to go back to what we were before, and you represent that,’” Abbas recalled. He was flattered, and the pay was double what he was making at that point, but he refused, believing he didn’t have the experience or expertise necessary for the position, and he didn’t want to hurt his team members by making the wrong decisions.

The board refused his refusal. “They said, ‘You’re going to do it because you said no the first time,’” Abbas recalls. “‘You understand what’s at stake here.”

Abbas started working on building his skill set and doing what he thought was best for the company, but he says he made a crucial mistake. While he focused on expanding the facilities, hiring rapidly, and working on financial metrics and risk management, he took his focus off the thing that first brought him into the company: the culture.

Phrases such as, “This place doesn’t feel like it used to,” “We have too many rules and procedures,” “We are getting too corporate,” and “It’s no fun” started to be heard around the company. “And now that I was the leader, the employees weren’t saying it about the company; they were saying it about me.”

At the time, Abbas says he wasn’t listening to them in the right way. “You begin to build a bit of animosity over this,” he says, “because I’m thinking to myself, ‘I’m trying to be focused on these things that are really important — you just don’t understand.’ But all they’re saying is that, ‘We’d just like a little time with you. When was the last time you came down to the bar with us?’ It had been months. They were absolutely correct.”

Still, Abbas didn’t make culture a priority until he got a young manager knocked on his door and provided him with a lesson he never forgot.

The Moment of Clarity

“He comes in and tells me, ‘I’ve got this employee who’s really good at his job. He’s probably one of the best I’ve ever seen. But he’s terribly rude and disrespectful.’” This employee would refuse to train people new to the company, making statements such as, “I had to learn this on my own,” and “I’m not here to wipe your nose. Welcome to the company.”

This employee also refused to listen to new ideas and would bad mouth the manager behind his back every chance he got, undermining his authority and that of the company’s leadership. “I knew this about the person, and I also knew this: I knew that he was incredibly talented,” Abbas says. “To this day, he’s still the best CNC machinist I’ve ever seen in my life. He sees things in three dimensions. He’s just a very gifted human being.”

He was also, Abbas says, a terrible teammate. “I need to fire him,” the manager finally said. “Do you want this area fixed? I can’t have him working here anymore.”

Abbas says he then called the human resources department and got the employee’s latest performance evaluation. “I opened the review to the last page, and it said he ‘performs as expected, meeting expectations,’” he says. Abbas began to see a problem with the process when he saw that the manager who had just asked for the man to be fired had signed that evaluation.

“So, I had somebody sitting in front of me who says, ‘I need to fire this person, because they’re just so awful in our environment,’” Abbas says. “But the review that I just gave him said, ‘You’re doing fine.’ I thought to myself, ‘Well, we can’t do that. You can’t tell somebody that they’re doing fine and then, a bit later, tell them they’re fired.’”

The problem, Abbas discovered, was how the evaluation weighed all the factors that go into an employee’s performance.

“I looked at his scores,” he says. “Job knowledge — 5, quality of work — 5, amount of work done — 5, attitude — 1, teamwork — 1. It was all fives and ones. Add it all together and divide, and the average came up to three.”

In other words, satisfactory.

But Addas discovered that was just the tip of the problem. “I asked the HR manager about everyone’s reviews, and that’s what they all looked like. Our company was reviewing almost 100 employees. At about four hours per employee, that was 400 hours just wasted.”

This system, Abbas saw, hid the areas where employees shined, but also where they needed to improve. By marking everyone as “average,” the company’s leadership was blind to what was truly happening.

Come back Tuesday for Part 3 of this series, where we’ll detail the better way Abbas discovered to evaluate his team members. For Part 1, click HERE.

Have a question or comment? E-mail our editor Dave Davis at [email protected].